Tuesday, 6 September 2016

The Imitation Game

I was mildly irked a little while ago when a journalist insinuated that I played 'too much like Buddy Rich'. Here is a classic hallmark of a writer who lacks background knowledge and analytical depth in his choice of subject matter, in this instance, me. You would be right in thinking that to be compared with one of the very best and most influential drummers of all time would be a huge compliment, which of course it is, but in this instance the tone was strangely pejorative especially when you consider that I was playing big band music.

It was curious and somewhat left handed compliment for the want of a better expression. Any drummer who has even the slightest inclination towards playing big band music needs a thorough grounding in, and understanding of Rich's playing. Whether or not his intense, driving swing and death defying hands are something you aspire to in your own playing is neither here nor there. The fact is you need to know about it, it's that simple.

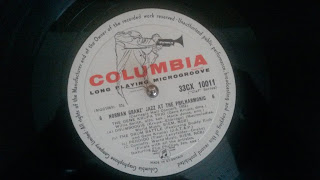

Buddy was my second big drumming influence after Joe Morello, and Louie Bellson was third. In addition though there were all kinds of other players whose sounds and styles I absorbed early on. A shortlist would most likely consist of Shelly Manne, Kenny Clare, Cozy Cole, Don Lamond, Alvin Stoller (uncredited on a Sinatra Lp) Max Roach, Philly Joe Jones, Ed Thigpen, Sonny Payne, Jake Hanna and of course the one and only Gene Krupa.

Formative influences at the point in your playing life when you are a novice are the influences that will stay with you forever. These were the drummers on my Dad's vinyls, and I got something from all of them. I came to this music long before I had any real affinity for pop or rock.

Undoubtedly irrespective of your chosen instrument the players you admire will have a varying level of impact upon you, from "mmmmmm" to "WHOAAAA!!!!

In my life there have been a small number of drummers whose playing had that most profound effect; they include Joe Morello, Buddy Rich, Mel Lewis, Tony Williams, Steve Gadd and Vinnie Colaiuta (in chronological order of discovery), but it's important to stress I got a million more ideas from a few thousand other players.

My goal as a musician has always been simply this; to keep the legacy of the departed grand masters alive and to incorporate contemporary ideas and influences as well. If Krupa and Rich were still alive who would they be checking out?

I'm not one of those players who climb on the vintage bandwagon either, steadfastly refusing to play any equipment manufactured after 1945. Some of these players hide behind thin cymbals and woodblocks, and whilst they play well they play perfectly well there is often a lack of serious depth or understanding. You don't need to be a monster technician by today’s standards to play some Krupa licks but that's not really the point, and sometimes this can look like an easy berth for the aspiring carpetbagger, and all too frequently the end result falls in some hinterland between pastiche and parody. Use of calf heads in this day and age is borderline fraudulent affectation.

Buddy Rich on the other hand, that's a way bigger ask. I know of a number of guys in the USA who play more like Buddy than Buddy did. That's quite an achievement in itself, the downside of which is that they come in for bucket loads of 'talent envy' from less able competitors and deranged kith and kin. Dogs don't bark at parked cars, but why do these guys do it? Because they can, that's why. The haters would do it too if only they had the requisite talent and courage to step up to the plate.

Putting the negativity very much on one side where it truly belongs, I believe that younger players can get so much from this, as the older guys who were fortunate enough to hear the legends play live can often pass something on. None of us are going to get to hear John Bonham in the flesh, but to witness a musician who totally understands the style and play it convincingly is history coming to life. The musicians who started all this stuff in the first place were doing it for many reasons, among which was, to quote Papa Jo Jones, "for the babies".

Seek out the musicians who have been around the block a few times. The players with some serious miles on the clock who have seen and heard things you have yet to find out about.

For almost a decade I have been performing other people's music as a bandleader. This was a significant volte face from my original ethos which was to gather together more contemporary (and a high perentage of original) music which I hoped would appeal to the broadest demographic without going down the well-worn nostaligia path. The big record labels sniffed around briefly, and at one point it looked as though we might have been on the path to bring uncompromising big band music to a mainstream audience. We didn't as it happened. The price of talk was at a near all time low and promises dont pay the bills.

After seeing one or two big band covers on Youtube I felt I could do certain music a little more justice and became aware that there was an audience out there who wanted to hear paricular things played the way they were intended. In addition the reality was that I was getting good offers to revisit the recent past. It's music that I like and know inside out so there was nothing to lose. It's great to look at historic performances on Youtube but to hear it live is a whole different deal, I caved in and everybody loved it! However despite countless requests I have never released any recordings of my big band playing classic repertoire. The whole point is for you to be in a room and to experience the living impact of the music. The original recordings are readily available and fantastic, so why would I bother?

Drumming is part of the language of music, and our first steps in learning any language consist of replicating what we have heard. When certain musical repertoire is being interpreted it is incumbent upon us to play the drums with an authenticity that serves the music, so that it will sound as close to what the original composer, arranger or performer had in mind. That's not to say that one should replicate original drum parts note for note; my remit is always to adapt my playing so it sounds as appropriate as possible in any given context, and that is where influences can possibly serve us best.

Which brings me to the somewhat controversial subject of drum covers.

The internet is awash with drummers of every stripe playing along to other people's music, as well as the countless backing tracks from all the indispensible play along packages of the last quarter century. It's great, don't get me wrong. The internet provides a unique platfrom for up and coming (as well as established) musicians to show the world what they can do. Posting videos of my band opened doors that would never have been openable, or possibly would not have existed under the old regime.

However, an internet post is forever so you may want to factor this in before clicking the upload button. Last year's 200bpm double bass drum shred might just be giving out the wrong message to future musical collaborators. Music performance is almost entirely a team effort, and it doesn't matter what form, style or genre you choose (or several if you prefer), everybody out there who is lookng for a drummer all wants the same thing.

They want us to help them sound good, or sound better. A simple universal law.

Think about it. Who ever (knowingly) booked a rhythm section secure in the knowledge that it would make their music sound worse than usual? You won't get the call if the leader likes a subtle, background player rather than a high energy butt-kicker. Hands up, I tend to default to the latter but am capable of both. So bear this in mind; two minutes on Youtube might not say everything about you as a musician, but the wrong two minutes might inadvertantly separate you from the opportunity of a lifetime.

Lastly there is the grey area where education and drum covers overlap. There are a great many very capable drummers out there who are constantly posting videos consisting of analysis of style of the master players both past and present. Some of them are really very good but I sigh the weariest of sighs when I see posts with titles such as

'Buddy Rich's left hand explained'.

It isn't Buddy Rich's left hand, it's yours. The only person who could really explain Buddy's left hand would be Buddy, were he still amongst us, and if he were the chances are he might decline or make a pithy and evasive remark along the lines of the famous Jim Chapin and Joe Morello at the Edison hotel anecdote. So take a moment to think before presenting opinion and conjecture as fact.

Interestingly I saw a capable and noted drum tutor demonstarting a lick he attributed to a popular contemporary drummer. The first comment on the Youtube post was the drummer himself objecting to his name being used and demanding that the video be removed. Tricky. Far better to present something 'in the style of' or 'inspired by' rather than a mere replication of somebody else's creativity.

The whole point of copying those we admire is to learn and grow, and the best way in which we can do so is to develop our knowledge and understanding of the instrument, take the things we most admire, take them apart and 'reverse engineer' them. Once you have done that you will be ready to reassemble the ideas your own way, in other words rather than copping and replicating a single pattern or idea you could have a whole system with tens of thousands of variations all your own. or as I say to my students...........

Look beyond the lick.

Incidentally, I'm hoping that another player will come to prominence who will make me go "WHOAAAA!!! again. It would be good to get that feeling one more time.

Thursday, 1 September 2016

When Will We Be Famous?

Usain Bolt. What a guy. His supreme and yet somehow implicit (rather than explicit) confidence that he is totally at the top of his game coupled with a real talent for self deprecation is a sure sign of mastery. A serious man who knows the importance of not taking himself too seriously.

That one of the most celebrated athletes in the world wears his fame so lightly is a characteristic I admire tremendously.

Why then do I occasionally run into musicians who are trying so very hard to be so important? Just the very fact of being able to pursue this career is something for which we should all be quietly appreciative, particularly given that our industry is not entirely without the over entitled few, whose lack of perceived success is always someone else's fault. Perhaps the near total lack of material wealth and approbation on offer to players of instruments is a root cause of resentment which is sadly all too frequently aligned with addiction and self destruction.

I do stress 'quietly appreciative', though, as the 'honoured and humbled' brigade can get really tiresome really quickly too. Easy on the quasi Dickensian forelock touching please: you're talented, you worked hard, you stuck at it and you got there.

I must admit I did 'quietly appreciate' this the other day...

However I nearly gagged on my cappuccino some months ago when a capable but really not even slightly well known fellow drummer described himself as 'famous' in a Facebook post. I think he may have been attempting dark humour. I do hope so, as anyone dedicating their life to honing virtuoso instrumental skills had better not be expecting mainstream media coverage and megabuck paydays. Mr Warhol's promise of 15 minutes each seems ever more prescient and I suspect that while my back was turned I may have had mine already.

To more practical concerns therefore. Your bank balance will fare significantly better if you are fortunate enough to land a gig with a name artist, which brings me to the most frequently asked question from people outside the industry.

"Have you ever worked with anybody famous? "

This question is a key reason why I try to avoid talking about my work when in the company of non musicians.

The other big misapprehension is that we all live in huge detached houses in the home counties with expensive cars on the drive.

The reality of this business is a long way from what many people might assume.

In my 20s I became friends with a great British jazz drummer whose international profile was unequalled at the time. He was an inspiration and a favourite, watching him live was a turning point and made me want to be more than just a big band player. We became acquainted and he invited me to his home. I was surprised that the expected five bed detached with a carriage drive turned out to be a considerably more modest mid terrace, and that I had a better car than he did. This goes on to this day where even a small amount of industry profile is mistakenly equated to significant wealth. It isn't like that at all, we're all mostly trying to make a reasonable living, indeed arguably the most universally revered drummer alive today said in my hearing that he "couldn't afford to retire", (which is good news for the rest of us as we can still go see him play).

Of course it wasn't always like this.

Once upon there was an era when instrumentalists had borderline household name status, of which there can be no better example than Gene Krupa, who became a bona fide star in the United States and beyond in an era when instrumental virtuosity and popular appeal were more closely in alignment than at any time since. The musicians of the swing era were big names in their day, this continued for several decades after the birth of rock and pop music yet nowadays the instrumentalist is marginalised and ignored quite unlike anytime previously. The last truly 'famous' drummer was Ringo, and we're talking north of 50 years ago, which when you consider the impact that the sound of musical instruments makes on our daily lives is, in the words of the Velvettes, really saying something. Imagine a West End show or a Hollywood blockbuster without musicians, what a monochrome world it would be without the sounds we make.

Support your local instrumentalist!

The quid pro quo here is that if you are generous enough to do so we promise not to fill an entire set list with original compositions none of less than nine minutes duration.

For playing to be truly great it has to appeal to a non-specialist listener without compromising integrity. Tricky but not impossible.

My three key formative influences were demonstrably master players. Even if you know nothing about the art of drumming it is immediately obvious how great Joe Morello, Buddy Rich and Louie Bellson were/are. The generation who followed were every bit as gifted albeit perhaps a little less user friendly to the non specialist listener (reflecting the way in which jazz itself was evolving, nota bene). More recent decades have witnessed the growth of 'muso' music which is largely aimed at and appreciated by other instrumentalists, little or none of which has succeeded in escaping from the niche market, therefore not growing a new audience. That's why my big band hardly ever plays shows on Saturdays-almost all of our target audience will be out somewhere doing a gig of their own.

The diminishing profile for musicians in the wider world brings it's own set of problems. Smaller audience numbers mean promoters are understandably less willing to take a punt on new artists and less familiar material. The jazz tribute show has been with us for a long time it seems, but you don't have to go back much more than 20 years to find a time when this was very much in the minority and the players were the draw rather than the repertoire.

Another upshot of this is that a lot of players get sidelined, young and old alike. Even back in the 90s when the big band first began to get up a head of steam and was generating significant interest I was always disappointed by the attitude of certain promoters towards us. Back then the average age of the band was far lower and a comparative lack of big name credits seemed to deter some bookers even though a great many of the then lineup had broken into West End shows and studio work. In short, an aggregation of superb talent was regularly sidelined because we didn’t have associations with famous names and I was (at that time anyway) doggedly determined to carve out a repertoire which was 'ours'.

The need to be approved of and to have audience appeal is more a part of the equation than ever. With dispiritingly increasing regularity I see gig billings which read more like a CV, with each musician's name followed by a list of credits, from the truly hip to the utterly irrelevant and downright absurd. Who a musician has played with is not a true measure of his/her value or ability, it's as much to do with circumstance as anything. A player with a background in the session world (such as it still is) is inevitably more likely to have played with more 'names' than someone from a different background. Does it make them a better player? Of course not.

My penchant towards the sardonic means that it is only a matter of time before you will see me listed as

Pete Cater (Val Doonican, Max Bygraves)

Does this sort of thing really get any extra bums on seats? Or does it have the negative effect of insulting the intelligence of the audience by presuming an ovine reaction along the lines of "Oh he must be good, he did two tours with Rose Marie", (don't remember? Lucky you) and therein lies the problem; if you had the gig with Dollar or Brother Beyond way back when it's not going to mean a whole lot now, and several decades more experience has hopefully made you a better player. Nothing goes out of date quite like a CV.

The other key marker for a measure of a musician's ability is received wisdom. In the upper echelons there is often not a great deal to separate one player from another, a lot boils down to personal preference and sheer good fortune. Very often a musician is considered to be a superior player because "someone else said so", even some of my industry colleagues are guilty of this. Truthfully it all boils down to perception, which thanks to social media is something over which we can have possibly more control than ever. Here I can speak with authority having become prominent only since my mid 40s. Whilst I continue to strive for improvement I'm not twice the player I was when relatively unknown.

To prove my point here's some ultra low definition video from almost twenty years ago.

I owe my later career almost entirely to the internet, and the people with video cameras who captured some of this footage. Thanks to platforms like YouTube and MySpace I was able to establish and to some extent control my online presence to the point where roughly ten years since my first video upload I get professional opportunities I could only have dreamed of in years past.

Note this carefully because you can do it too, and it has nothing to do with associations with big name artists.

The downside of all this is that musicianship is woefully undervalued, possibly more than at any time in recent history. We are faced with the option of giving away a certain amount of content at no charge, but to put a positive spin on that remember the importance of accumulation via speculation. Quite possibly the wandering minstrels of days gone by didn't have it any worse. Apart from a brief glimpse during the Proms there is very little presence in mainstream media, so we have to create our own playing field. The upside of the internet age is that it's much easier to get yourself out there and slowly the scene is actually becoming more meritocratic. The days when you weren't a part of the in crowd unless you drank and played golf with the right members of the funny handshake brigade are happily very much in the fourth time repeat of the coda.

In conclusion, don't make value judgements on a musician's ability only because he or she played with someone famous.

So when I get asked the question I just say yes and leave it at that.

For more information about clinics, masterclasses, personal tuition, guest appearances or any of my bands click here.

*********************************************************************************

Postscript on the life changing power of the internet.

The www had perhaps the biggest unintended consequence when I discovered the UK National Drum Fair whilst browsing. I took myself off there only to find Ian Palmer was doing a clinic. I hadn't seen him in years and that day he asked me about taking part in an event he was planning some twelve months hence. The rest most of you know, but the moral of this digression is that the 'right place, right time' theory works best when you make the effort to put yourself in the right place.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)