2016 has been a memorable year for all sorts of reasons.

Personally, ever the nonconformist, I've had a great year, just like 2015 before it, and plans are in place to keep forging ahead in 2017. So ambitious it makes you sick.

As we head towards the beginning of yet another journey round the sun this January 1st I am minded to think of just how many well known faces have taken their last curtain call in the preceding twelvemonth. This is quite possibly the single most hot topic de nos jours; social media is littered with asinine comments along the lines of "2016, go and do one". As surely as the route of the orbit is predetermined we know that it will be the beginning of the last go round for a great many more; some household names, others known only to their immediate family and circle of friends. Whichever category you fall into you might consider resolving to make 2017 a year of achievement. It doesn't matter what, and indeed you may not yet know what it is you seek to achieve, but keep your eyes and ears open as much as you can and before too long your goal will make itself known. This seemingly uncommonly high celebrity death rate should serve as a salutory reminder to all of us to stop putting things off, be a 'doer' not a 'talker', and if you are harbouring unfulfilled ambitions try to do one small thing every day to take even the tiniest step towards achieving your goals. Make a list. Keep a diary. Chart your progress. It's easy.

Another strategy I began to deploy far later in life than I should have is to take as much responsibility as is reasonably possible for what is going on in your world. Obviously precious things like good health and prosperity can not be absolutely controlled, but there are a great many areas in which we can take charge a little more. Now and then I will get the occasional student who has every excuse in the book why they haven't advanced as players or in the industry: not enough time, nowhere to practice, not enough money, not living in the right area, not knowing the right people and so on. Believe you me I've heard them all and more besides.

As the years have passed I have slowly realised that we have more control over our destinity than we would perhaps like to admit to. The easy cop-out is to blame circumstances and other people, rather than actually grasping the nettle (not always easy) to make changes. We live in a peaceful nation which offers both huge opportunity and a safety net if you're unlucky enough to suffer misfortune. Here in the UK the sky really is the limit, arguably more so than anywhere else in the world. That's worth bearing in mind. If you can make it here you can make it anywhere, to paraphrase Mr Sinatra. I'll come back to him later.

The days when a self-selecting elite had supreme control in all sorts of areas of society may finally be heading towards the dustbin of history where they belong. All my professional life I have been a busy, working musician and I managed to establish myself without the advantages of family wealth or nepotism. After a delayed, slow and haphazard start (another story altogether) I managed to make some reasonable headway in the industry and by my mid 30s was busy as well as having a successful band which had forged a decent reputation on the UK jazz scene.

Then everything changed. I started to harness the opportunities provided by the internet explosion. It didn’t happen overnight, it was very definitely a few small steps in the first instance. Some videos that had been captured a few years previously found their way on to Youtube and I started to connect with new people in the UK and further afield.

The launch of the lamented Drummer magazine (another loss in the past year) presented me with the opportunity of a feature interview as I was doing a project that was deemed 'trendy' at the time. Further web surfing alerted me to the existence of the UK National Drum Fair; a visit to which reunited me with my old friend Ian Palmer, who asked me to participate in a spectacular concert the following September. The same day Jason Keyte confirmed an offer for my big band to appear in concert in East Anglia the following April. On that occasion another old friend Jack Parnell was in the audience, and a recommendation from Jack led to a most fruitful business relationship with Derek Boulton who set me up with a tour headlining theatres across the UK.

All this because I bought my first computer aged 38.

The road to world domination started with a dial up modem.

You may not be seeking worldwide fame and wealth although I hope some of you are, (one friend is determined to win an academy award; talk about aiming high!) If you are then please don't be misled by reality TV; the deal is that you have to be able to do something, ideally to an extremly high standard. Otherwise, when you have the mansions, the cars and enough bling to sink a ship, if the money won't stop rolling in what on earth are you going to do now that all your goals have been achieved?

This is what is so great about being a player. No matter how far you advance in the industry there's always something left to achieve. Every day someone else is coming up with the latest new idea (as you should be too!) and the possibilities continue to grow exponentially. Quite a while ago I realised that this is what truly motivates me, and having risen to a position in the industry where I am able to share this knowledge with fellow players the world over is truly the most delicious payback for a fair amount of hard work invested up front with no guarantee of a return.

To put it another way there's no such thing as 'good enough'. You try your best on any given day and hope to improve upon it next time around. Truly we are only as good as our last performance, although in the interests of positivity I prefer to be as good as my next performance.

The recent sad passing of George Michael, amongst the latest in an uncommonly large number of well known faces to have passed during the course of this year, actually got me thinking whether international superstardom is all it's cracked up to be. I neither met him nor worked with him though a great many acquaintances did so. He wrote a significant number of iconic pop songs which I neither especially like nor dislike. During my 'professional apprenticship' in the mid to late 80s these songs were much covered in the line of work and many of them will be forever associated with holiday camps, cruise ships, and provincial pantomimes, and playing them was never objectionable.

Since Michael's untimely passing much has been made of his deeply admirable clandestine generosity and philanthropy by stealth. Without doubt there are many more revelations still to come and it is deeply to his credit that all of this giving was done from behind a veil of secrecy. Contrast that with the self regarding alignment to fashionable causes displayed by international irritants such as Bono and Geldof with tiresome regularity. Their conceit in the supremacy of their own opinions and the regularity of same makes me think of the wonderful and sincerely missed AA Gill's description of a well-known Britsh actress as a 'three flush floater'. The 'luvvies' as the popular press delight in dubbing them, do love to hand down virtuous commandments from the ratified and gilded seclusion of the hills of Primrose and Notting. Sometimes I can't help wishing they would use their influence in a more positive way, perhaps away from the glare of publicity. Either that or just stick to acting. Yes, you Benedict. Your opinions are of no greater worth than a cab driver. Probably a whole lot less come to think of it. Don’t do good in order merely to look good, or worse, make a pitch to join Vicky B on the honours list.

Fame is one of those qualities like expertise; it’s almost invariably bestowed upon us by others rather than self proclaimed (unless you can afford a great publicist). Working overseas recently brought an interesting insight.

"Let me introduce a famous drummer", said the CEO of an internationally renowned musical instrument company in a hotel bar a few months ago. I was amused and flattered but at the same time intrigued by how some of the people present behaved differently when they thought I was some sort of a 'big deal'; the same people I had passed by every day for a week in the lobby or the taxi line without raising an eyebrow were suddenly hanging on my every word. Funny thing, perception.

The obituary columns of the media have been littered over the years with obsequies for those who have risen to the top only to find themselves unable to deal with the consequences of stardom. I hesitate to refer to these consequences as pressures as there are many who take worldwide acclaim in their stride, but fame is one of those things in life for which nothing can prepare you. Writing songs or practicing your instrument in your bedroom will help you hone your craft but there is no training course that can prepare you for suddenly being of interest to complete strangers.

If you haven't already done so I suggest you read the open letter to George Michael written by the then 74 year old Frank Sinatra. Sinatra's words are witty, insightful and kind but the subtext is ineluctably clear throughout and it is simply the old adage,

"Be careful what you wish for".

It's also worth adding that if you wish for it, don’t pretend it happened by accident. One acquaintance who has achieved a little notoriety in his chosen field is a frequent social media bore claiming that the recognition he has received is some sort of happy accident, which as anyone who knows him even slightly knows is complete nonsense. He's been planning this for years. The only people who achieve fame completely by accident are almost invariably the victims of something terrible.

Similarly another very talented friend had a brush with success in the afterglow of somebody else's limelight. When the limelight faded my friend was left with a sense of entitlement which manifested in all sorts of ways from professional gamesmanship to talking loudly on aeroplanes. Everybody thought he was a great guy, I saw past the facade.

If you are feeling ambitious about what 2017 holds for you, and I hope you are, don't let your ambition be a source of embarrassment. And when you finally hit one of your targets perhaps you might do us a favour and go easy on the 'humbled and grateful'. You're talented, you worked hard and you reached your goal, but don't forget that although the drinks may be free at Club Tropicana sometimes there's a price to be paid elsewhere. Make sure you are ready. It might be your year.

Friday, 30 December 2016

Friday, 23 December 2016

You Never Forget Your First

With Christmas seemigly in jeopardy at the time of writing, here's the story of a game changing gift from the early 1970s.

A little while ago I was sitting with some distinguished friends in the instrument industry and discussing the somewhat changeable climate for those who depend on manufacturing or selling drums for their living.

I made the following observation;

“We live in a time when there are more drum sets in the world than ever before, and that number is increasing every day”.

The point being that drummers have got more choice in terms of both range of options and availability of product thus making it ever more challenging for manufacturers to keep coming up with new lines that will get some traction in the market.

It wasn’t always the case though. My late father was a good and busy semi pro player all his life. As a teenager he grew out of the first drums (no name snare and bass drum plus one small suspended cymbal) and sought to upgrade. Youngsters of the day were regularly fobbed off by the instrument shop staff with extremely scarce professional equipment on display; interest in a Dominion Ace would be met with “Reserved, awaiting collection” or “in for repair”. The Gig Shop in Birmingham was the most notorious offender, where a quasi-Masonic cabal got first dibs on anything worthwhile that came in to stock.

That left one primary avenue for hopefully finding some drum treasure, the classified ads of the local paper, and eventually after countless tram rides across inner city Birmingham Dad eventually stumbled upon a four piece Ajax set in gold sparkle (‘glitter gold’ as they called it then) and this became his first professional quality drum set. Not until the late 40s did British drum manufacturing really get back up to a speed anywhere close to satisfying the demand for product.

By today’s standards this seems ridiculous, where copious quantities of drums from shiny new to pedigree vintage are just a couple of clicks away. If your budget allows you can start a collection; have a different drum configuration to suit every musical circumstance and more snare drums than there are days in the month. The days when working drummers had one set of drums and that was it are behind us.

Even in my early days as a player good used equipment was relatively scarce and would get snapped up in a moment. I had inherited my dad’s practice kit as a starting point.

This consisted of a Windsor single tension bass drum measuring about 22 x 8, with a matching (grey paint) single headed tom approximately 10 x 7. An Ajax 12 x 10 tom in blue pearl stood in for a floor tom, the snare was a truly vile Olympic Discus which resisted every attempt to make it sound even half way decent and a riveted 20” Ajax ride cymbal was the cherry on the cake. No hi hats, these didn’t arrive until my 9th birthday in the shape of a pair of 14” Zyns.

The arrival of the hi hat cymbals marked a turning point and it was clear that my development as a fledgling player merited something a little more sophisticated and robust if I was to advance significantly further on my quest for worldwide recognition. I had fallen head over heels for a chrome over wood Gretsch ‘Name Band’ outfit in the window of Ringway Music but clearly that was out of reach, and so regular trawls round the music shops of the city, primarily Yardley’s, George Clay, Kay Westworth’s and the afore mentioned Ringway. Dad wasn’t a fan of Jones and Crossland or Woodroffe’s for reasons I never found out. The easy option would have been a brand new Premier or Beverley, good quality and in plentiful supply, but my dad’s generation all aspired to the great American brands with Ludwig at the top of the tree with Rogers, Slingerland and Gretsch in equal second place. Anyone who was around then will confirm that Ludwig was the brand everybody wanted to be seen to be playing; Ringo, for the pop drummers, Joe Morello for the jazzers. Not even Buddy Rich’s affiliation with Slingerland from 1968 onwards could assail Ludwig’s stranglehold on the top end of the market.

But as the 70s dawned the stardust began to fade on the Ludwig brand. The reason? Quality control.

All of a sudden the crown was up for grabs and it was Rogers who seemed to have the traction and almost overnight became the brand of choice.

Meanwhile the Cater tradition of scouring the small ads in the Birmingham Mail in search of decent drums had proved fruitless. Up to £120 was only yielding rather so-so pre international Autocrats and the occasional gaudy Rose Morris. Used Ludwigs, Haymans, more recent Premiers and British Rogers were over budget, so my dad played his ace. Without a trade in he was able to get a healthy discount on a silver sparkle Rogers Starlighter and handed down his 1964 oyster blue super classic to me.

That set of drums defined my early days as a player. Most of my early adventures in the world of music were done to the sound of the Ludwigs. My first proper recording session in a proper studio (BBC Maida Vale studio 6, December 1979) which resulted in me winning the Jack Parnell drum award in the BBC National big Band competition. I thought that was it; and that my passage to the upper echelons of the British drum industry was assured; (and so it was, but it didn’t begin to happen for another 27 years). Incidentally, my performance from the ensuing gala concert was left out of the subsequent Radio 2 broadcast, so in the interests of completeness here is my 16 year old self.

https://soundcloud.com/petecaterbigband/back-to-the-barracks

Interestingly my first visit to a television studio was done on my dad’s Rogers. The reason being that the Ludwig was in residence at the NEC Birmingham. I was cutting school to play a 15 act international circus and earning more than my headmaster was. A baptism of fire, but my unshakeable confidence stood me in good stead, albeit with rather too many fills. A subsequent return to the small screen shows the Ludwigs proving their worth. Follow the link and the keen eyed among you will note the addition of a second floor tom. All my big band heroes of that period (start with Buddy Rich, Louie Bellson and Butch Miles then work your way down) featured the second 16 x 16 and I was determined to emulate the drum layout of the players whose playing I also sought to emulate.

https://youtu.be/kRSNM7qBjMg

Finding the additional drum in matching oyster blue was a virtually impossible task. Irrespective of it being far and away the most ubiquitous finish on drums exported to the UK, odd drums and add-ons were all but unheard of. Eventually an orphan floor tom turned up, badly re-wrapped in plain black, so for a while the second floor was mismatched, decades before Bill Stewart did something similar.

Unbelievably after considerable research by my dad some original 1960s oyster blue wrap surfaced. Eddie Ryan, then based at 90 Long Acre, Covent Garden, was the saviour. The shell was stripped of all its fittings and dispatched. Furthermore there was sufficient wrap left over to build me a canister throne so my oyster blue Krupa/Buddy set up was complete.

By this point several of the original mounting blocks (with the thread tapped into the metal itself) had failed and were replaced with the later hook and eye design, in addition to which was the somewhat predictable addition of a second cymbal arm on the bass drum for the inevitable 8 inch splash. Imitate then innovate as they say. Mission half accomplished, so to speak. A barnstorming tour of Germany with the Midlands Youth Jazz Orchestra followed, as well as a return to Golders Green Hippodrome marking a second successive victory in the BBC National Big Band Competition. The broadcast was recorded on my eighteenth birthday and the drum feature can be heard here.

https://youtu.be/XN92aNCn72E

Note the slightly unusual snare sound. I achieved this by using a split bottom head for several weeks without realising!

As I’ve said elsewhere the career prospects for an aspiring 18 year old straight ahead jazz/big band drummer were practically non-existent in the big-haired, shoulder-padded early 80’s. Truthfully there are more opportunities to play that kind of music at a professional level now than there were then. Call it the Rat Pack/Buble effect for the want of a better expression. In spite of which my very small degree of notoriety brought me to the attention of Sabian cymbals and the UK distributors of Slingerland, and for the first time I had the much sought after ‘deal’.

Other than a summer spent playing in a Mecca ballroom residency, the Super Classic was being used increasingly infrequently and my remaining time in the MYJO showcased the Slingerland with the Ludwig being relegated to more mundane tasks, which is silly really because the Slingerland wasn’t a patch on it. Incidentally, drum solos of the era were often of a duration that would have left Ken Dodd in awestruck admiration.

Still the wheel turned further still and I had woken up to the needs of being a working professional player, and as all young pros should, the importance of playing according to what the industry requires. I augmented the Ludwig with a couple of Roto Toms briefly but the writing was on the wall and in late 1984 I acquired a used Yamaha 9000GA in natural wood which I wish I still owned, in sizes 10 x 8, 12 x 8, 13 x 9, 16 x 16 and 14 x 22. Thus dawned a whole new era in my playing as I stepped out into the wider professional world leaving the Ludwig at my parents’ house where it resides to this day.

A little while before my affiliation with Premier and thereafter the British Drum Company, I took the super classic out on a Dave Brubeck tribute show and it played as well as ever. It’s a family heirloom brim full of significance and personal history. It was my first proper, grown-up drum set and will stay with me forever, and hopefully get a play one day again soon, because there’s nothing quite like your first is there?

Sunday, 27 November 2016

Big Band Drumming part 3

BIG BAND DRUMMING PART 3

Last time we looked at some fundamentals of timekeeping in the big band rhythm section. Having discussed the ‘what’ and ‘how’ we should also give some consideration to the ‘why’.

What does timekeeping do in the big band? Why is comping helpful? What do fills do? Answer: they enable to horn players to play their figures in exactly the right places. Fills and solos within the context of a big band arrangement serve exactly the same purpose as keeping time on the cymbals. All that rhythmic information serves the purpose of maintaining the pulse and energy in the music. Your playing should have a rock solid foundation enabling you to control the band by means of time and dynamics. Fills and solos absolutely must have a strong, clear feeling of time. Don’t be tempted to throw in unnecessary and irrelevant chops, which only serve to muddy the waters.

One of the most important musical relationships in the big band is between drums and lead trumpet. You should pay very close attention to what the lead trumpet plays; not just for time, but also phrasing. When we play figures with the brass section our drumming should reflect what the horns are playing in two key areas. Firstly: articulation. When the horns play a short (staccato) note we should choose a sound which matches, e.g. snare, bass drum, rim shot, stick on stick, choked crash cymbal, closed hi hat etc.

If you they play a longer note, pick a longer sound, e.g. crash cymbal, ride cymbal, open hi hat, buzz roll etc.

When reading figures off charts it’s important to observe accents and articulation markings as well as note values. A quarter note with a ^ accent will almost always be played shorter than an eighth note with a > accent. These markings will help you to anticipate the phrasing of the ensemble is likely to be.

Very often drum charts may be a little short on markings indicating phrasing and articulation. As you rehearse each chart listen to what the band is playing and add accents and markings to help remember what the band is doing so you can match their figures accordingly. Always mark charts with pencil only. Use of ink may result in J K Simons style outbursts from your bandleader. Carry a 2B pencil in your stick bag. A real pro has a sharpener as well.

Secondly: dynamics and register. The drummer should always reflect the dynamics of the horn sections and importantly, the register in which they are playing. Be sure to read the dynamic markings as well as the rhythmic notation. Don’t play ‘ff’ (fortissimo = very loud) if everyone else is ‘mp’ (mezzo piano + moderately quiet). Lower pitches in the band should be matched with lower more subtle sound choices on the kit. E.g. the snare blends well with the trumpets, but trombones are better ‘pitch matched’ with the bass drum.

When the big band has rhythmic phrases to play it’s your task to ‘set up’ the figures.

There are all sorts of different rhythmic possibilities here, but certain of them are especially commonplace; none more so than the ‘and of 1’. Notated on the chart it will look like this.

On the accompanying video you’ll see me demonstrate this, and I’m using mostly swung eighth and triplet patterns, (and occasionally sixteenth notes) in varying sequences.

Practice these yourself and find combinations of single and double strokes, which fit the bill. Once you have evolved the sticking orchestrate it around the drums. The most common sequence of orchestration is snare, high tom, floor tom. Overused this can get to sound a little predictable. Try variations such as starting from the floor tom, going to the small tom and finishing on the snare. An ascending sequence of pitches can be a musical breath of fresh air. Often I’ll start on the snare, move to the small tom and come back to the snare. Again this resolves the phrase in a less predictable fashion. In short, don’t go and buy more toms until you’ve exploited all the tonal variations of a basic set of drums.

It’s unusual for an arranger to specify what we drummers are going to put where. That part is almost always up to you, and one of the hallmarks of a good, reading drummer is the ability to interpret rhythmic notation in a musical fashion. Don’t make the mistake of playing the entire line on the snare. That demonstrates good reading ability but can be lacking in musicality. A good big band drummer listens to what the other musicians are playing and should reflect melodic movement in the band. Just by sharing out a rhythmic line between the snare and bass drum you can create a melodic sense, which you won’t get from just using a single sound source.

One of the key tasks of the big band drummer is to be able to fill between figures. You will often find yourself with anything from a couple of beats to a number of bar to fill. These fills act as links in the music, which enable one ensemble phrase to be seamlessly connected to the next. Go for strong rhythmic figures which will bind the various sections of the music together rather than as much terminal velocity chops as you can squeeze into the available space.

You can see how each time I manage to come up with different permutations of rhythms, stickings and orchestrations, so rather than using muscle memory and playing licks I am genuinely improvising.

At our medium swing tempo a mixture of eighth notes and triplets would be ideal. A quarter note on the third beat of the bar immediately prior to the horns on the fourth beat will provide a clear and solid end to the fill, helping everybody to place the next phrase perfectly in time.

Remember that a change of dynamics, i.e. a crescendo or diminuendo through a fill can create musical tension and drama and really control the musical energy of the band.

Five key figures, 1950-1970s

Mel Lewis (1929-1990)

A constant favourite with musicians, Mel Lewis blended the subtlety of small group jazz with the fire and swing of the big band, most notably with the orchestra he co-led with trumpeter and composer Thad Jones. Lewis swung with intensity and depth of feeling that has seldom been equalled and his swing feel remains a benchmark and inspiration to all serious students of the genre. Calfskin heads and old, dark, Turkish K Zildjians helped him create his signature sound. Magnificently opinionated and outspoken, Mel was a man of great integrity who stayed true to his musical ideals throughout his entire career. A meeting with him in the USA in 1985 changed my direction when without being asked, he sat down at the drums and demonstrated his unique ride cymbal approach, which I promptly appropriated. The Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra made its debut on Monday February 7th 1966 at the Village Vanguard in New York City, a weekly residency that the Vanguard Jazz Orchestra maintains to this day. Mel’s earlier work with the Terry Gibbs ‘Dream Band’ is also essential listening.

Key tracks

‘Mean What You Say’ (‘Presenting the Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra’)

‘Cherry Juice’ (Thad Jones & Mel Lewis, ‘New Life’)

‘Blues in a Minute’ (Thad Jones and Mel Lewis, ‘Potpourri’)

Jake Hanna (1931-2010)

The powerhouse drummer who most memorably fired up Woody Herman’s Herd in the early to mid 60’s, check out the Jazz 625 TV show on YouTube to see Hanna at his best. A swinging and driving player who had a level of versatility comparable to Mel Lewis in that he was at home with any combination from a trio to a big band, and whilst a more than capable soloist he totally eschewed chops of any kind in later years playing a two piece kit with a couple of ride cymbals. Following his tenure with Herman Jake spent many years in the LA studio scene and in his later career played jazz with small groups in preference to big bands. To spend time in Jake’s company was a pleasure. He had jokes and anecdotes about everybody and anybody in the business all delivered in his distinctive New England accent. A great musician and a huge personality both on stage and off.

Key tracks

‘Hallelujah Time’, (Woody Herman ’64)

‘Better Get it in Your Soul’ (Woody Herman ‘Encore’)

‘Apple Honey’ (Woody Herman, ‘Woody’s Big Band Goodies’)

Nick Ceroli (1939-1985)

First came to public attention as the ‘live’ drummer with Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass. (Hal Blaine played on many of the band’s recordings, which were described by Buddy Rich as “almost good music”). Nick Ceroli was a constant presence on American television for many years as the drummer in Mort Lindsey’s house band on the Merv Griffin show. More importantly he maintained an active role on the jazz and big band scene in Southern California. There are terrific small band jazz recordings out there featuring Ceroli with saxophonists Art Pepper (‘Collections’) and Pete Christlieb (‘Live at Dino’s). Ceroli’s trademark in the big band rhythm section was his china cymbal, known as ‘the trash can’. You can hear him at his swinging best on four standout albums with Bob Florence’s big band in the late 70’s and early 80’s. Nick Ceroli passed away in 1985 at just 45 years of age.

Key tracks

‘Nobody’s Human’ (Bob Florence Limited Edition ‘Soaring’)

‘Rhythm and Blues’ (Bob Florence Limited Edition ‘Magic Time’)

Carmelo’s by the Freeway (Bob Florence big band ‘Westlake’)

Sonny Payne (1926-1979)

Of all the great drummers of the ‘new testament’ Count Basie band, Sonny Payne was a driving, swinging, technically gifted player with few equals. Payne is often best remembered for his showmanship and stick tricks, but we shouldn’t be diverted from the ineluctable fact that he was a true master of the big band style who was entirely deserving of his place alongside the Buddys and Louies of this world. Check out the entire Atomic Mr Basie album and see how musical and understated he could be. The Basie band’s studio collaborations with Frank Sinatra are masterpieces too, although on the seminal Sinatra at the sands recording there are times when Sonny strays dangerously close to overplaying territory. For me one of the outstanding key elements of his style was his ability to make amazingly dramatic changes in dynamics in four or eight bar fills and really control the volume of the ensemble. That he was first choice as a permanent replacement when Buddy Rich left Harry James’ band in 1966 is indicative of the esteem in which he was rightfully held. Another giant who left far too soon.

Key tracks

‘Fantail’, (The Atomic Mr Basie)

‘Half Moon Street’, (Count Basie ‘Chairman of the Board’)

‘Counter Block’, (Count Basie ‘Breakfast Dance and Barbecue’)

Charlie Persip (1929-)

One of the few true giants still with us today, I first was introduced to Persip’s work at a very early age courtesy of a drum compilation vinyl LP. Immediately I was captivated by his sound and style, he was speaking the be bop language of Max Roach and Philly Joe Jones but combining it with speed, chops and stamina to rival Buddy Rich. In addition he had an amazing bass drum pedal technique and was able to achieve speed that many of his contemporaries required two bass drums to equal. Although attaining prominence primarily via his work with Dizzy Gillespie’s big band between 1955 and 58 he managed to avoid to all too frequent typecasting as ‘just a big band drummer’ (tell me about it!!) and recorded in small groups with a wide ranging and distinguished assortment of jazz stars of the era. A bandleader in his own right, Persip’s recordings with his own large and small groups are well worth seeking out.

Key tracks

‘The Champ’, (Dizzy Gillespie, ‘World Statesman’)

‘The Song is You’, (Charles Persip and the Jazz Statesmen)

‘Drum Solo’, (Gretsch Drum Night at Birdland)

Tuesday, 6 September 2016

The Imitation Game

I was mildly irked a little while ago when a journalist insinuated that I played 'too much like Buddy Rich'. Here is a classic hallmark of a writer who lacks background knowledge and analytical depth in his choice of subject matter, in this instance, me. You would be right in thinking that to be compared with one of the very best and most influential drummers of all time would be a huge compliment, which of course it is, but in this instance the tone was strangely pejorative especially when you consider that I was playing big band music.

It was curious and somewhat left handed compliment for the want of a better expression. Any drummer who has even the slightest inclination towards playing big band music needs a thorough grounding in, and understanding of Rich's playing. Whether or not his intense, driving swing and death defying hands are something you aspire to in your own playing is neither here nor there. The fact is you need to know about it, it's that simple.

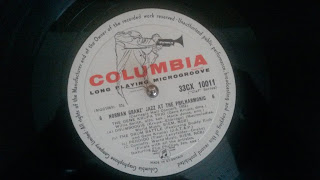

Buddy was my second big drumming influence after Joe Morello, and Louie Bellson was third. In addition though there were all kinds of other players whose sounds and styles I absorbed early on. A shortlist would most likely consist of Shelly Manne, Kenny Clare, Cozy Cole, Don Lamond, Alvin Stoller (uncredited on a Sinatra Lp) Max Roach, Philly Joe Jones, Ed Thigpen, Sonny Payne, Jake Hanna and of course the one and only Gene Krupa.

Formative influences at the point in your playing life when you are a novice are the influences that will stay with you forever. These were the drummers on my Dad's vinyls, and I got something from all of them. I came to this music long before I had any real affinity for pop or rock.

Undoubtedly irrespective of your chosen instrument the players you admire will have a varying level of impact upon you, from "mmmmmm" to "WHOAAAA!!!!

In my life there have been a small number of drummers whose playing had that most profound effect; they include Joe Morello, Buddy Rich, Mel Lewis, Tony Williams, Steve Gadd and Vinnie Colaiuta (in chronological order of discovery), but it's important to stress I got a million more ideas from a few thousand other players.

My goal as a musician has always been simply this; to keep the legacy of the departed grand masters alive and to incorporate contemporary ideas and influences as well. If Krupa and Rich were still alive who would they be checking out?

I'm not one of those players who climb on the vintage bandwagon either, steadfastly refusing to play any equipment manufactured after 1945. Some of these players hide behind thin cymbals and woodblocks, and whilst they play well they play perfectly well there is often a lack of serious depth or understanding. You don't need to be a monster technician by today’s standards to play some Krupa licks but that's not really the point, and sometimes this can look like an easy berth for the aspiring carpetbagger, and all too frequently the end result falls in some hinterland between pastiche and parody. Use of calf heads in this day and age is borderline fraudulent affectation.

Buddy Rich on the other hand, that's a way bigger ask. I know of a number of guys in the USA who play more like Buddy than Buddy did. That's quite an achievement in itself, the downside of which is that they come in for bucket loads of 'talent envy' from less able competitors and deranged kith and kin. Dogs don't bark at parked cars, but why do these guys do it? Because they can, that's why. The haters would do it too if only they had the requisite talent and courage to step up to the plate.

Putting the negativity very much on one side where it truly belongs, I believe that younger players can get so much from this, as the older guys who were fortunate enough to hear the legends play live can often pass something on. None of us are going to get to hear John Bonham in the flesh, but to witness a musician who totally understands the style and play it convincingly is history coming to life. The musicians who started all this stuff in the first place were doing it for many reasons, among which was, to quote Papa Jo Jones, "for the babies".

Seek out the musicians who have been around the block a few times. The players with some serious miles on the clock who have seen and heard things you have yet to find out about.

For almost a decade I have been performing other people's music as a bandleader. This was a significant volte face from my original ethos which was to gather together more contemporary (and a high perentage of original) music which I hoped would appeal to the broadest demographic without going down the well-worn nostaligia path. The big record labels sniffed around briefly, and at one point it looked as though we might have been on the path to bring uncompromising big band music to a mainstream audience. We didn't as it happened. The price of talk was at a near all time low and promises dont pay the bills.

After seeing one or two big band covers on Youtube I felt I could do certain music a little more justice and became aware that there was an audience out there who wanted to hear paricular things played the way they were intended. In addition the reality was that I was getting good offers to revisit the recent past. It's music that I like and know inside out so there was nothing to lose. It's great to look at historic performances on Youtube but to hear it live is a whole different deal, I caved in and everybody loved it! However despite countless requests I have never released any recordings of my big band playing classic repertoire. The whole point is for you to be in a room and to experience the living impact of the music. The original recordings are readily available and fantastic, so why would I bother?

Drumming is part of the language of music, and our first steps in learning any language consist of replicating what we have heard. When certain musical repertoire is being interpreted it is incumbent upon us to play the drums with an authenticity that serves the music, so that it will sound as close to what the original composer, arranger or performer had in mind. That's not to say that one should replicate original drum parts note for note; my remit is always to adapt my playing so it sounds as appropriate as possible in any given context, and that is where influences can possibly serve us best.

Which brings me to the somewhat controversial subject of drum covers.

The internet is awash with drummers of every stripe playing along to other people's music, as well as the countless backing tracks from all the indispensible play along packages of the last quarter century. It's great, don't get me wrong. The internet provides a unique platfrom for up and coming (as well as established) musicians to show the world what they can do. Posting videos of my band opened doors that would never have been openable, or possibly would not have existed under the old regime.

However, an internet post is forever so you may want to factor this in before clicking the upload button. Last year's 200bpm double bass drum shred might just be giving out the wrong message to future musical collaborators. Music performance is almost entirely a team effort, and it doesn't matter what form, style or genre you choose (or several if you prefer), everybody out there who is lookng for a drummer all wants the same thing.

They want us to help them sound good, or sound better. A simple universal law.

Think about it. Who ever (knowingly) booked a rhythm section secure in the knowledge that it would make their music sound worse than usual? You won't get the call if the leader likes a subtle, background player rather than a high energy butt-kicker. Hands up, I tend to default to the latter but am capable of both. So bear this in mind; two minutes on Youtube might not say everything about you as a musician, but the wrong two minutes might inadvertantly separate you from the opportunity of a lifetime.

Lastly there is the grey area where education and drum covers overlap. There are a great many very capable drummers out there who are constantly posting videos consisting of analysis of style of the master players both past and present. Some of them are really very good but I sigh the weariest of sighs when I see posts with titles such as

'Buddy Rich's left hand explained'.

It isn't Buddy Rich's left hand, it's yours. The only person who could really explain Buddy's left hand would be Buddy, were he still amongst us, and if he were the chances are he might decline or make a pithy and evasive remark along the lines of the famous Jim Chapin and Joe Morello at the Edison hotel anecdote. So take a moment to think before presenting opinion and conjecture as fact.

Interestingly I saw a capable and noted drum tutor demonstarting a lick he attributed to a popular contemporary drummer. The first comment on the Youtube post was the drummer himself objecting to his name being used and demanding that the video be removed. Tricky. Far better to present something 'in the style of' or 'inspired by' rather than a mere replication of somebody else's creativity.

The whole point of copying those we admire is to learn and grow, and the best way in which we can do so is to develop our knowledge and understanding of the instrument, take the things we most admire, take them apart and 'reverse engineer' them. Once you have done that you will be ready to reassemble the ideas your own way, in other words rather than copping and replicating a single pattern or idea you could have a whole system with tens of thousands of variations all your own. or as I say to my students...........

Look beyond the lick.

Incidentally, I'm hoping that another player will come to prominence who will make me go "WHOAAAA!!! again. It would be good to get that feeling one more time.

Thursday, 1 September 2016

When Will We Be Famous?

Usain Bolt. What a guy. His supreme and yet somehow implicit (rather than explicit) confidence that he is totally at the top of his game coupled with a real talent for self deprecation is a sure sign of mastery. A serious man who knows the importance of not taking himself too seriously.

That one of the most celebrated athletes in the world wears his fame so lightly is a characteristic I admire tremendously.

Why then do I occasionally run into musicians who are trying so very hard to be so important? Just the very fact of being able to pursue this career is something for which we should all be quietly appreciative, particularly given that our industry is not entirely without the over entitled few, whose lack of perceived success is always someone else's fault. Perhaps the near total lack of material wealth and approbation on offer to players of instruments is a root cause of resentment which is sadly all too frequently aligned with addiction and self destruction.

I do stress 'quietly appreciative', though, as the 'honoured and humbled' brigade can get really tiresome really quickly too. Easy on the quasi Dickensian forelock touching please: you're talented, you worked hard, you stuck at it and you got there.

I must admit I did 'quietly appreciate' this the other day...

However I nearly gagged on my cappuccino some months ago when a capable but really not even slightly well known fellow drummer described himself as 'famous' in a Facebook post. I think he may have been attempting dark humour. I do hope so, as anyone dedicating their life to honing virtuoso instrumental skills had better not be expecting mainstream media coverage and megabuck paydays. Mr Warhol's promise of 15 minutes each seems ever more prescient and I suspect that while my back was turned I may have had mine already.

To more practical concerns therefore. Your bank balance will fare significantly better if you are fortunate enough to land a gig with a name artist, which brings me to the most frequently asked question from people outside the industry.

"Have you ever worked with anybody famous? "

This question is a key reason why I try to avoid talking about my work when in the company of non musicians.

The other big misapprehension is that we all live in huge detached houses in the home counties with expensive cars on the drive.

The reality of this business is a long way from what many people might assume.

In my 20s I became friends with a great British jazz drummer whose international profile was unequalled at the time. He was an inspiration and a favourite, watching him live was a turning point and made me want to be more than just a big band player. We became acquainted and he invited me to his home. I was surprised that the expected five bed detached with a carriage drive turned out to be a considerably more modest mid terrace, and that I had a better car than he did. This goes on to this day where even a small amount of industry profile is mistakenly equated to significant wealth. It isn't like that at all, we're all mostly trying to make a reasonable living, indeed arguably the most universally revered drummer alive today said in my hearing that he "couldn't afford to retire", (which is good news for the rest of us as we can still go see him play).

Of course it wasn't always like this.

Once upon there was an era when instrumentalists had borderline household name status, of which there can be no better example than Gene Krupa, who became a bona fide star in the United States and beyond in an era when instrumental virtuosity and popular appeal were more closely in alignment than at any time since. The musicians of the swing era were big names in their day, this continued for several decades after the birth of rock and pop music yet nowadays the instrumentalist is marginalised and ignored quite unlike anytime previously. The last truly 'famous' drummer was Ringo, and we're talking north of 50 years ago, which when you consider the impact that the sound of musical instruments makes on our daily lives is, in the words of the Velvettes, really saying something. Imagine a West End show or a Hollywood blockbuster without musicians, what a monochrome world it would be without the sounds we make.

Support your local instrumentalist!

The quid pro quo here is that if you are generous enough to do so we promise not to fill an entire set list with original compositions none of less than nine minutes duration.

For playing to be truly great it has to appeal to a non-specialist listener without compromising integrity. Tricky but not impossible.

My three key formative influences were demonstrably master players. Even if you know nothing about the art of drumming it is immediately obvious how great Joe Morello, Buddy Rich and Louie Bellson were/are. The generation who followed were every bit as gifted albeit perhaps a little less user friendly to the non specialist listener (reflecting the way in which jazz itself was evolving, nota bene). More recent decades have witnessed the growth of 'muso' music which is largely aimed at and appreciated by other instrumentalists, little or none of which has succeeded in escaping from the niche market, therefore not growing a new audience. That's why my big band hardly ever plays shows on Saturdays-almost all of our target audience will be out somewhere doing a gig of their own.

The diminishing profile for musicians in the wider world brings it's own set of problems. Smaller audience numbers mean promoters are understandably less willing to take a punt on new artists and less familiar material. The jazz tribute show has been with us for a long time it seems, but you don't have to go back much more than 20 years to find a time when this was very much in the minority and the players were the draw rather than the repertoire.

Another upshot of this is that a lot of players get sidelined, young and old alike. Even back in the 90s when the big band first began to get up a head of steam and was generating significant interest I was always disappointed by the attitude of certain promoters towards us. Back then the average age of the band was far lower and a comparative lack of big name credits seemed to deter some bookers even though a great many of the then lineup had broken into West End shows and studio work. In short, an aggregation of superb talent was regularly sidelined because we didn’t have associations with famous names and I was (at that time anyway) doggedly determined to carve out a repertoire which was 'ours'.

The need to be approved of and to have audience appeal is more a part of the equation than ever. With dispiritingly increasing regularity I see gig billings which read more like a CV, with each musician's name followed by a list of credits, from the truly hip to the utterly irrelevant and downright absurd. Who a musician has played with is not a true measure of his/her value or ability, it's as much to do with circumstance as anything. A player with a background in the session world (such as it still is) is inevitably more likely to have played with more 'names' than someone from a different background. Does it make them a better player? Of course not.

My penchant towards the sardonic means that it is only a matter of time before you will see me listed as

Pete Cater (Val Doonican, Max Bygraves)

Does this sort of thing really get any extra bums on seats? Or does it have the negative effect of insulting the intelligence of the audience by presuming an ovine reaction along the lines of "Oh he must be good, he did two tours with Rose Marie", (don't remember? Lucky you) and therein lies the problem; if you had the gig with Dollar or Brother Beyond way back when it's not going to mean a whole lot now, and several decades more experience has hopefully made you a better player. Nothing goes out of date quite like a CV.

The other key marker for a measure of a musician's ability is received wisdom. In the upper echelons there is often not a great deal to separate one player from another, a lot boils down to personal preference and sheer good fortune. Very often a musician is considered to be a superior player because "someone else said so", even some of my industry colleagues are guilty of this. Truthfully it all boils down to perception, which thanks to social media is something over which we can have possibly more control than ever. Here I can speak with authority having become prominent only since my mid 40s. Whilst I continue to strive for improvement I'm not twice the player I was when relatively unknown.

To prove my point here's some ultra low definition video from almost twenty years ago.

I owe my later career almost entirely to the internet, and the people with video cameras who captured some of this footage. Thanks to platforms like YouTube and MySpace I was able to establish and to some extent control my online presence to the point where roughly ten years since my first video upload I get professional opportunities I could only have dreamed of in years past.

Note this carefully because you can do it too, and it has nothing to do with associations with big name artists.

The downside of all this is that musicianship is woefully undervalued, possibly more than at any time in recent history. We are faced with the option of giving away a certain amount of content at no charge, but to put a positive spin on that remember the importance of accumulation via speculation. Quite possibly the wandering minstrels of days gone by didn't have it any worse. Apart from a brief glimpse during the Proms there is very little presence in mainstream media, so we have to create our own playing field. The upside of the internet age is that it's much easier to get yourself out there and slowly the scene is actually becoming more meritocratic. The days when you weren't a part of the in crowd unless you drank and played golf with the right members of the funny handshake brigade are happily very much in the fourth time repeat of the coda.

In conclusion, don't make value judgements on a musician's ability only because he or she played with someone famous.

So when I get asked the question I just say yes and leave it at that.

For more information about clinics, masterclasses, personal tuition, guest appearances or any of my bands click here.

*********************************************************************************

Postscript on the life changing power of the internet.

The www had perhaps the biggest unintended consequence when I discovered the UK National Drum Fair whilst browsing. I took myself off there only to find Ian Palmer was doing a clinic. I hadn't seen him in years and that day he asked me about taking part in an event he was planning some twelve months hence. The rest most of you know, but the moral of this digression is that the 'right place, right time' theory works best when you make the effort to put yourself in the right place.

Wednesday, 3 August 2016

Comping or Composition?

The standard of drummers worldwide has never been higher. Once upon a time the most ambitious drummers would make a beeline for New York because if you could "make it there" etc etc.

These days it's a whole new ball game. The availability of resources online, in print and via knowlegable and experienced tutors has helped to raise the general standard of playing to unprecedented levels.

It's particularly pleasing to see and hear so many great young jazz drummers in the UK who are speaking the language in far greater numbers and with more fluency than any time in history, and believe you me they are not getting into it for the money and glamour. So what happened? It would be both unfair and impossible to point to one single reason for this explosion of talent but in 1994 the jazz drumming game changed forever with the publication of John Riley's 'Art of Bop Drumming'.

I have mixed feelings about drum books and often feel that the imperative is purely financial. There are serial repeat offender authors out there who seem to have no profile other than their name on a book cover. Just like teaching it is not a consolation prize for the lack of a playing career. Often on clinics and drum shows I joke about this by saying

"Nobody ever wrote a drum book to make the world a better place".

It could be argued however that John Riley did just that. Art of Bop does not contain a single wasted word or gratuitously hard or irrelevant exercise. This book and its successor 'Beyond Bop Drumming' will give you all the essential tools to unleash the jazz drummer within you. Equally important are the listening recommendations and analysis of classic recordings.

Working through some of the early sections of the book with an older student yesterday he asked me about the comping exercises and how I would apply them in the context of actual performance. Riley's book will give you all the idiomatic phrases you could possibly wish for, but what happens on the bandstand when the chips are down and all your drum books are at home in the practice room?

Answer......learn tunes.

Comping in the rhythm section is just as much about improvisation as trading fours or eights, taking a chorus or playing an 'open' solo. Anyone who has studied with me knows how opposed I am to the concept of muscle memory, I prefer to connect with the music and play spontaneously. Of course we all have ideas that get repeated, but that's a big part of how you sign your name when you play.

My strategy to get the ideas flowing either as a team player in the section or a soloist is to think of a melody I know well. I'll use it as a frame of reference to play off. There are many advantages to doing this.

If you are tracking the melody of a tune you know inside out it is highly unlikely that you will lose your place in the form. Singing a melody to yourself enables you to take a step closer to music whereas slavishly counting bars and beats is taking a step away from music, diminishing your attention to what is being played not just by the other musicians but also by you. Taking a chorus on a 32 bar form will be much more interesting if you are thinking about the melody of Joyspring (Clifford Brown) rather than thinking (1234, 2234, 3234, 4234).

Working with fake books and lead sheets works a treat, in addition to which you can use the rhythmic notation in front of you in a Ted Reed/Alan Dawson type of way.

Also, compose when you comp. The jazz drummer's left hand is for the most part deploying six different rhythmic motifs, so it's good strategy to practice them at a sufficiently slow tempo in order to be able to think which one you might use next. As you get better at this you will be able to raise the bar and be able to play 'in the moment' as distinct from trotting out pre-learned ideas from muscle memory. Develop the confidence to leave the toolbox in the back of the car, or better still, at home.

Even if you have no aspiration to play jazz drums at all this concept is in no way genre specific. I create grooves and fills in all styles of music by borrowing the rhythms of known melodies and orchestrating them between my hands and feet.

That said I think every drummer can benefit from studying the art of jazz. Don't forget that the drum set as we know it today was invented by and for jazz musicians, and if it hadn't have been for jazz who knows what kind of percussion would be prevalent in music today. Maybe we'd all be sitting atop wooden boxes and slapping them with our bare hands. (Oh....hang on....)

Not only that but every time I go on to instagram I see 'drum selfies' I so often see the 'one up, two down' configuration which originated with Gene Krupa.

In order to be a monster today it's well worth knowing what went before.

For more information about clinics, masterclasses, personal tuition, guest appearances or any of my bands click here.

These days it's a whole new ball game. The availability of resources online, in print and via knowlegable and experienced tutors has helped to raise the general standard of playing to unprecedented levels.

It's particularly pleasing to see and hear so many great young jazz drummers in the UK who are speaking the language in far greater numbers and with more fluency than any time in history, and believe you me they are not getting into it for the money and glamour. So what happened? It would be both unfair and impossible to point to one single reason for this explosion of talent but in 1994 the jazz drumming game changed forever with the publication of John Riley's 'Art of Bop Drumming'.

I have mixed feelings about drum books and often feel that the imperative is purely financial. There are serial repeat offender authors out there who seem to have no profile other than their name on a book cover. Just like teaching it is not a consolation prize for the lack of a playing career. Often on clinics and drum shows I joke about this by saying

"Nobody ever wrote a drum book to make the world a better place".

It could be argued however that John Riley did just that. Art of Bop does not contain a single wasted word or gratuitously hard or irrelevant exercise. This book and its successor 'Beyond Bop Drumming' will give you all the essential tools to unleash the jazz drummer within you. Equally important are the listening recommendations and analysis of classic recordings.

Working through some of the early sections of the book with an older student yesterday he asked me about the comping exercises and how I would apply them in the context of actual performance. Riley's book will give you all the idiomatic phrases you could possibly wish for, but what happens on the bandstand when the chips are down and all your drum books are at home in the practice room?

Answer......learn tunes.

Comping in the rhythm section is just as much about improvisation as trading fours or eights, taking a chorus or playing an 'open' solo. Anyone who has studied with me knows how opposed I am to the concept of muscle memory, I prefer to connect with the music and play spontaneously. Of course we all have ideas that get repeated, but that's a big part of how you sign your name when you play.

My strategy to get the ideas flowing either as a team player in the section or a soloist is to think of a melody I know well. I'll use it as a frame of reference to play off. There are many advantages to doing this.

If you are tracking the melody of a tune you know inside out it is highly unlikely that you will lose your place in the form. Singing a melody to yourself enables you to take a step closer to music whereas slavishly counting bars and beats is taking a step away from music, diminishing your attention to what is being played not just by the other musicians but also by you. Taking a chorus on a 32 bar form will be much more interesting if you are thinking about the melody of Joyspring (Clifford Brown) rather than thinking (1234, 2234, 3234, 4234).

Working with fake books and lead sheets works a treat, in addition to which you can use the rhythmic notation in front of you in a Ted Reed/Alan Dawson type of way.

Also, compose when you comp. The jazz drummer's left hand is for the most part deploying six different rhythmic motifs, so it's good strategy to practice them at a sufficiently slow tempo in order to be able to think which one you might use next. As you get better at this you will be able to raise the bar and be able to play 'in the moment' as distinct from trotting out pre-learned ideas from muscle memory. Develop the confidence to leave the toolbox in the back of the car, or better still, at home.

Even if you have no aspiration to play jazz drums at all this concept is in no way genre specific. I create grooves and fills in all styles of music by borrowing the rhythms of known melodies and orchestrating them between my hands and feet.

That said I think every drummer can benefit from studying the art of jazz. Don't forget that the drum set as we know it today was invented by and for jazz musicians, and if it hadn't have been for jazz who knows what kind of percussion would be prevalent in music today. Maybe we'd all be sitting atop wooden boxes and slapping them with our bare hands. (Oh....hang on....)

Not only that but every time I go on to instagram I see 'drum selfies' I so often see the 'one up, two down' configuration which originated with Gene Krupa.

In order to be a monster today it's well worth knowing what went before.

For more information about clinics, masterclasses, personal tuition, guest appearances or any of my bands click here.

Friday, 29 July 2016

It's A Deal

Earlier this week I was in the company of drummers. I'm seldom happier than when I'm in the company of drummers, the feeling of fraternal shared experience is very strong and really quite unique.

A couple of conversations particularly stuck with me. Several glasses were enjoyed in the company of one of the UK's justifiably most in demand freelance drummers. I commented that it must be a pleasant departure to talk to another drummer without the inevitable 'hustle' coming into the equation. My friend said that he is besieged by approaches from drummers looking for deps, gig recommendations etc multiple times every day. Personally I rarely dep gigs out unless I can absolutely avoid it. I choose the work I want to do where assignments tick a minimum number of specific boxes, and having made the commitment I stick by it. More than once in my years as a bandleader I have had been on the receiving end of feeble excuses because someone got offered a gig that paid a tenner more.

The grand prize goes to the musician who told me he had to stay at home because he was having a new kitchen fitted.

On a Sunday.

Also it's worth bearing this in mind; when someone books a specific musician to do a specific gig it's because they want 'that guy', and if 'that guy' is not available they will call 'that other guy' who is next on their list. Rarely if ever will they ask 'that guy' for a recommendation so remember this and don't be a nuisance.

If you play well enough people cannot possibly ignore you.

Things have rarely if ever happened over night and in the modern, congested industry things take longer than ever to move forward.

Take care of things musically and personally, handle your public profile appropriately and before you know it you will be getting the calls because you are 'that guy', after all the years of being 'some guy', which is how it starts for everybody.

OK, now it's time to own up.

How many young (and not so young) players reading this have a drum endorsement and a feature in a magazine at or near the top of their wish list?

A little recognition can go a long way and very often compensates for the years of effort and sacrifice, especially if as a wide eyed youngster you were drawn to a genre of music which is notoriously poorly paid, (yes, me!)

However, another word to the wise if I may.

Also this week it was a pleasure to spend time in the company of a British drum industry legend. An artist relations guy who is the best in the business and justifiably universally admired and respected.

He spends half his working life having to read emails that begin thus;

"My band is about to get signed".

"I am a 15 year old session drummer".

Similar advice holds good yet again. Instrument manufacturers and distributors have to make tiny budgets go a very long way and your introductory email is little more than a nuisance. If you are going to be of interest to the companies then you are already on their radar whether you realise it or not, and if they haven't noticed you yet keep doing the right thing until they do, because if you do it well enough for long enough they surely will. And when they notice you and you get to where you want to be, don't forget to keep taking care of business. It's a small industry and news travels fast, but bad news is at its destination before good news has got its shoes on.

Just like with getting gigs, go out there and network, get your videos uploaded, buy a ticket to the key drum events, get yourself down there and above all...........

Be nice.

Do that for long enough and to paraphrase the old saying, you'll be important too.

For more information about clinics, masterclasses, personal tuition, guest appearances or any of my bands click here

Thursday, 28 July 2016

Wood. You Believe It.

Sometimes it's the really simple things that make the difference, and this little piece of simplicity provokes a disproportionately high level of curiosity so I shall attempt to explain.

As I tend to play largely acoustically resonance and projection are key, and I tune my drums for a bright, wide open sound without the extremes of over tuning favoured by some jazz drummers. To my mind a bass drum is a bass drum and should be in an appropriate register not sounding like a 16 inch floor tom.

So, bright, open sounding drums is the thing for me. One thing that is far more difficult to control though is the physical response of the drums in different acoustic settings, and as a drummer for whom technical facility is an absolute requirement of the musical context in which I regularly play, tuning for stick response is as important as tuning for sound. That means bottom heads a little tighter than top heads because if they are vibrating at a higher frequency the air moving inside the drum will maximise the response from the playing side.

However, you can spend all day fine tuning the instruments but if you get to work to find you are setting up on thick carpet that will suck all the life and brightness out of the drums. Sometimes in a challenging acoustic or in the studio that can be just what is needed, but for me a responsive snare is an absolute.

Anytime you get to play acoustic music in a beautiful concert hall on a wooden stage the drums sound and respond at their best. I remember vividly an afternoon concert at Muse Ark Hall in Japan, a more beautifully crafted and precision engineered performance space I have rarely if ever seen, and it brought out the very best in me as a player.

Fast forward a few years and I was in the Battersea branch of Homebase and they had offcuts of oak flooring for 50p each. On a whim I bought three of them and the difference in the snare drum response was incredible. Brighter, clearer and much faster, so no matter where I'm playing, be it on a squelchy carpet, in a marquee, outdoors set up on grass (the worst! ) my snare drum sound and hand technique go everywhere with me. On those occasions when I'm playing a house kit and the wood floor stays at home the difference is extraordinary, but for the most part I have my own go anywhere, portable concert hall stage. £1.50 well spent.

For more information about clinics, masterclasses, personal tuition, guest appearances or any of my bands click here

Wednesday, 13 July 2016

Reputation, Reputation, Reputation

As a few of you may know in November last year I had the great good fortune to be asked to stand in for Harvey Mason at the 2015 London Drum Show. Harvey had an accident at home and sadly was unfit to fly. The brief was to be first artist on the main stage on the Saturday morning. I had heard a rumour on the Wednesday that something might be happening, but I didn't get confirmation until Thursday afternoon of what was already a very busy week. Too busy in fact to have time to be nervous about the drum show. I did it and it was pleasingly well received. I remembered that all important strategy for this kind of performance.

There are several hundred drummers out front and all their eyes are on you.

Remember though, that it is highly likely that the vast majority of them have only heard you play on possibly one or two occasions if at all. If they are hearing you for the tenth time the chances are that in their estimation you can do no wrong so that's fine as well.

Bearing that in mind stick to things you know are comfortable, familiar and that you play really well. Don't go too far out on a limb. Because we all know our own playing very well it has a familiarity. Don't let that sense of familiarity fool you into thinking that you might run the risk of being 'boring' to the audience. Don't worry. That won't happen.

In fact, this piece of advice (as my good friend Mike Scott pointed out to me earlier today) is pretty much bomb proof in 90% of musical environments. I can count on the fingers of one hand the times when I have been chastised for 'not being busy enough'. The great Harry 'Sweets' Edison once said I was too quiet (believe it or not) and a bandleader I worked for in a quartet on the QE2 once upbraided me for 'swinging too much'.

Having said that I did once see a legendary drummer do a clinic which was practically a word for word repetition of his tuition video from a couple of years previously, so if you are working in this sphere of the industry at all regularly it is important to keep things fresh.

Anyway, back to the London Drum Show. In the end the performance went very well and was pleasingly well received. I was satisfied to have met the challenge offered and to have delivered something at an appropriate standard . Quite an honour I'm sure you'll agree, but how do these things come about? Why me? With so many great players to choose from why was I the lucky so-and-so whose name got drawn out of the hat?

One word answer: reputation.

What the show organisers were looking for was a London based drummer with a profile, whose gear wasn't in an air cargo depot somewhere, who had plenty of drum show experience without suffering from the old enemy over-exposure, could be depended upon to show up at Olympia at stupid o'clock to get set up and isn't afraid of playing to a room full of drummers, including many international industry heavyweights.

So how do we go about creating a reputation? Some musicians seem to be skilled, proactive and switched on in this regard. It's a quality to incorporate early on and in today's congested and competitive industry it's more important than ever.

First you need to create the right kind of reputation and having done so you then need to manage it carefully. There follows a selection of dos and don'ts plus a few anecdotes which will hopefully serve to illustrate how the waters can get a bit choppy from time to time.

This simple advice will take you a long way until the vagaries of human nature get in the way. I admire the special cameraderie that exists amongst my many brass and woodwind playing colleagues, especially when a great new talent appears on the scene. When there are four or five players in a section they will make room for new talent whereas a drummer might find himself out of a job if the dep if just a bit too good. Believe me, it happens, so a solid, unfussy job will help you get established without frightening the living daylights out of your peers.

About twenty years ago I booked a noted UK drummer to cover three big band gigs for me. The gigs came and went, the job got done.

My dep called me to say thanks (nice touch, good manners) and proceeded to tell me that he thought he hadn't played all that well on the first gig but by the third he had come to feel very comfortable in the environment.

The next time I saw the bandleader he told quite a different story. His version was that my dep had done a great job on the first gig but by the third was putting in way too much and constantly overplaying.

You don't need me to explain that one to you do you?

I always advise students to aim to become versatile all-round players. Try not to become too closely associated with a very specific musical genre or playing style. As an aspiring professional drummer you need to take a look at what the industry is going to require from you and do your level best to meet those criteria . It's important to appeal to the maximum number of potential employers. Be prepared to play quite a lot of music you might not like all that much in order to establish a sure foothold in the scene. As Bob Moses said in his very valuable book Drum Wisdom, 'If you know music, you know the drums'. This is exactly what I did over 30 years ago when it became time to break out of the local scene in the Midlands.

In order to go out there, compete and make a living I had to broaden my perspective from being a big band/straight ahead jazz drummer. This involved absorbing other styles and making sure that my drums sounded right for what was the industry expectation of the mid 80's through to the mid 90's. Nailing down working with a click was an absolute necessity at that time, which fortunately I was able to get together very quickly, having been really quite bad at it on my first couple of attempts. Later I got the opportunity to specialise in the music and playing styles closest to my heart but in order to get to that point I served a lengthy apprenticeship which covered a whole range of music. A possible downside of being a specialist comes the risk of typecasting. As your profile increases people will often tend to associate you with the playing style and musical genre that has put you in the public eye. How flattering is it to be mentioned in the same breath as B***y R**h and others of that ilk and to have a profile in the industry for anything is a great compliment, but I think many readers might be surprised to know the wide range of things I have done in years gone by and sometimes still do today. If it pays properly and you're reasonably sure you can handle it always say yes. What doesn't kill you makes you stronger.

We all know the timeless anecdotes about some of the great 'character' drummers of times past; Keith Moon, Phil Seamen and all the rest. The stories are legendary and have passed into drummer folklore. Sadly though the lives of these big personalities often come off the rails and end in tragedy.

Once upon a time it was only the 'name' players whose indiscretions came to the attention of a wider public. Also the laws of supply and demand have made the shelf life of the hooligan muso a great deal shorter.

Social media has changed everything.

More than once I have seen good drummers (and other musicians) having very public disputes on Facebook and elsewhere (it used to be internet forum pages before that).

Social media is an extension of your performance and has added a whole new dimension to the concept of word of mouth. Starting wars, doing dirty laundry or having a meltdown in a public place (because it is) will always reflect badly on you, not your intended victim. You wouldn't strip naked on stage (I hope you wouldn't unless expressly contracted to do so) so think before you rant. A well thought out post can be compelling and effective, but that doesn't include calling someone a **** because they got a gig you felt should have been yours or you covet their drum endorsement.

People see posts and share posts. Don't push the self distruct button on your career with a hasty, drunken status update.

Be outstanding, but don't stand out for the wrong reasons

Inevitably at some time or another the green eyed monster will raise its ugly head. Keep a careful eye out for it.

"Whenever a friend succeeds, a little something in me dies". One of many classic Gore Vidal quotes but frequently all too true.

My late manager Derek Boulton said, as we sat in our office (a cafe in Dolphin Square) putting together the UK wide tribute to Buddy Rich tour which ran from January 2010 to September 2011, that I would be on the receiving end of some jealousy from one or two people out there in the industry, and how right he was. A fellow drummer besieged Derek with (very poor quality) publicity about his own (rather poor quality) big band project. He also called every theatre we were due to appear at saying